30% EV by 2030? Stop clapping. Start asking questions.

The Target vs. The Reality sets the scene for the headline without plan argument.

Hi Readers

Welcome to the new story of The Valuation Story for this week

I saw a headline last week that made me pause. “India targets 30% EV penetration by 2030.” The news was everywhere. Charts, TV debates, speeches.

But in my head, one question kept repeating…

Where is the plan?

Disclaimer

This is an educational reflection on EV adoption and risks in India. It’s not investment advice. Please do your own research before making financial decisions.

We love numbers in headlines. They’re clean. Inspiring. Easy to cheer for.

But numbers without a plan?

That’s just wishful thinking.

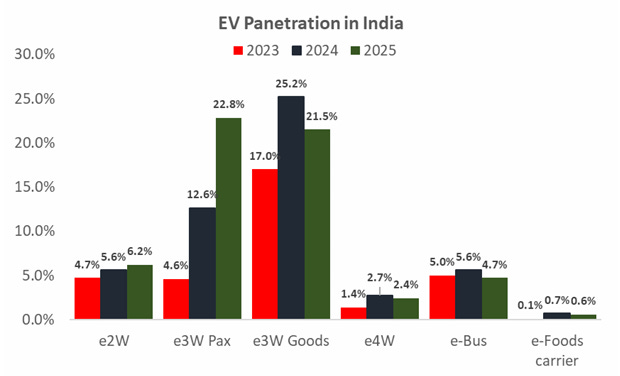

The first thing I noticed when I dug deeper: most of our EV “success” comes from scooters and rickshaws. E2W and E3W dominate the adoption chart.

Cars? Barely in the picture.

And that’s important, because private car adoption is a key driver if you want deep, sustainable EV penetration.

Scooters and rickshaws are easier to electrify, have lower costs, a short range, and require home charging. Cars demand more, bigger batteries, longer range, and more public charging.

That’s where the cracks start showing.

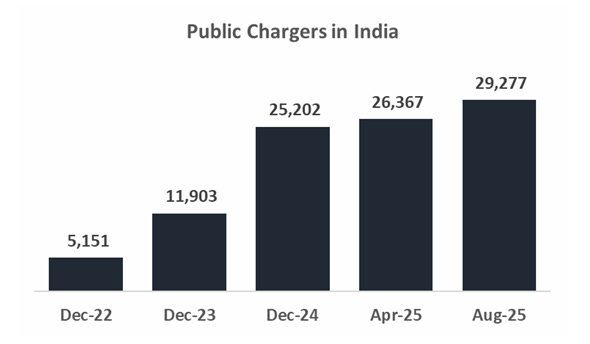

We are building chargers, yes. But almost half of them aren’t working.

Low uptime → low utilisation → poor unit economics.

In valuation terms, that means your fixed assets aren’t generating enough revenue. You’ve sunk capex into something that doesn’t generate the cash flows you modelled.

The problem isn’t just quantity — it’s quality.

We love to announce “X thousand chargers installed”, but an investor looks at “How many work?” Because that drives revenue, payback period, and ROI.

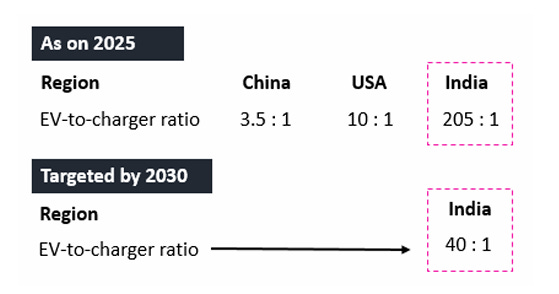

Then I looked at the density problem.

India has 1 public charger for roughly 205 EVs.

Compare that with China — 3 to 4 EVs per charger — or the US at 10 per charger.

Now imagine the ownership experience. In China, charging is like finding a grocery store. In India, it’s like finding a clean public toilet on the highway — rare, and not always functional.

That gap isn’t just bad for convenience. It’s a red flag for adoption curves. When the infrastructure lags, demand growth plateaus sooner. And that hits every revenue projection downstream, from charging companies to EV makers.

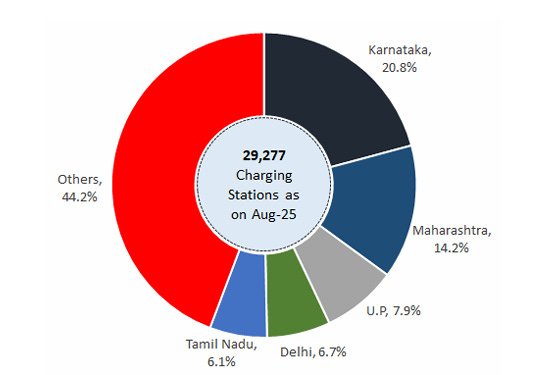

The concentration problem makes it worse.

Half of India’s chargers are in just 5 states: Karnataka, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, and Tamil Nadu.

That means most of the country is running on press releases, not plugs. If you live in Bihar or Assam, the EV dream isn’t just far, it’s invisible.

From a business lens, that’s market potential. If your TAM (total addressable market) is restricted to a few regions, your scale story weakens.

And then comes the supply chain choke point.

At least oil has OPEC. EV batteries have… China.

Over 70% of the battery cells we use are imported from one country. One geopolitical risk away from disruption.

What happens if that supply is cut or prices spike? Your cost structure explodes. Your margins collapse. Your DCF turns into a “pray cash flows recover” exercise.

Battery cost is already a hurdle.

It makes up around 40% of an EV’s total cost. Remove subsidies, and adoption slows sharply.

Yes, forecasts say battery costs will drop, but maybe only to around $90/kWh, not the $60–70/kWh that would make EVs truly competitive with ICE without subsidies.

And because we’re not making the cells domestically, we can’t control that cost curve.

The E4W (four-wheeler) segment is still stuck in first gear.

Why? Few affordable models, long charging times, high upfront cost, and weak highway infrastructure.

For many buyers, EVs make sense only for short urban commutes, not family road trips. And in India, cars are often bought for the “one car fits all needs” scenario. That makes the ICE option still more practical.

When consumers hesitate, sales forecasts turn unreliable. And valuation models hate unreliable demand inputs.

Even beyond cost and charging, the structural risks pile up.

We don’t have battery recycling at scale.

Our grid capacity isn’t ready for mass EV charging.

Policies shift with budgets and governments.

Battery-as-a-service is barely emerging.

Supply chain localisation is incomplete.

These are not “nice to haves”; they are the foundations for a sustainable EV economy. Without them, hitting 30% penetration might still happen, but sustaining it profitably is another story.

My valuation perspective

Government targets get baked into investor expectations. Companies raise capital, expand capacity, and price their shares as if those targets are guarantees.

But the cash flows depend on operational realities, chargers that work, batteries you can source reliably, and customers who buy without subsidies.

If even one of these assumptions breaks, the whole model shifts. Your IRR falls. Payback stretches. Risk premiums rise.

Here’s what I believed earlier:

That India’s EV growth curve would accelerate like China’s once the government sets a bold target and pushes incentives.

Here’s what I believe now:

Without solving infrastructure uptime, cost dependency, and E4W adoption, the curve could stall halfway. And that makes every forecast worth a second look.

So, what’s the takeaway?

A target is not a plan.

And a plan is not a forecast.

Before valuing an EV business in India, I now pressure-test three things:

Are the chargers operational?

Where is the battery supply coming from?

Is the growth in the segment that drives margins, or the one that just inflates volume numbers?

The 30% number might make a great headline.

But as an analyst, I’ve learned to read between the lines.

Because markets don’t reward headlines.

They reward cash flows.

Thank you for reading. I hope this helped you see the EV story beyond the surface.

Spend consciously. Value wisely. Live intentionally.

The Valuation Story

I will also recommend these insights: